Exhibition text:

Popular in the Middle Ages, bestiaries were collections of illustrated manuscripts compiling pseudo-scientific descriptions of Flora and, above all, Fauna.

The sometimes fanciful illustrations and descriptions were accompanied by moral narratives that reflected the belief that beings and things were part of a universe designed by God, each carrying a special meaning.

In short, the naturalists of the Middle Ages believed that the world itself is the word of God and that animals serve in the order of the world.

Many of the animals depicted are imaginary or bear little resemblance to real species. The monks who worked on these books had never actually seen the exotic animals they depicted, either because of their geographical remoteness or because they only existed in myth and folklore. Nevertheless, these encyclopaedias before their time were widely read and often considered as truth. At the time, magic, faith and science together formed reality.

Looking at the origins of the fantastic animals of the Middle Ages (such as the famous unicorn) brings us back to admiring the efforts made to explain the inexplicable. These creatures were created to give substance to rumours, to illustrate the unknown, and to tame it.

The unicorn exists because unicorn horns have been found—you don’t need to have seen one if you have its horn. For a long time, unicorn horns were thought to be the tusks of the narwhal, a marine animal whose rarity and limited habitat contributed to the persistence of this legend. The idea of a large horse with a horn in the middle of its forehead living in distant lands seemed a far more convincing and reassuring explanation than the existence of a 4 m tall sea animal with an ivory protuberance up to 3 m long.

In 1576, Elizabeth I of England is said to have paid 10,000 pounds for a horn, the equivalent of 600,000 euros today or the value of a castle at the time. People attributed virtues to these horns, such as the ability to neutralise poisons, and had goblets made from the ivory. It wasn't until 1704 that a link to the narwhal was established.

Nature abhors a void, as does the human mind, and we could laugh at the credulity of our ancestors if our era did not see the birth of new concepts such as alternative reality or the massive spread of Fake News driven by algorithms programmed to reinforce our view of the world.

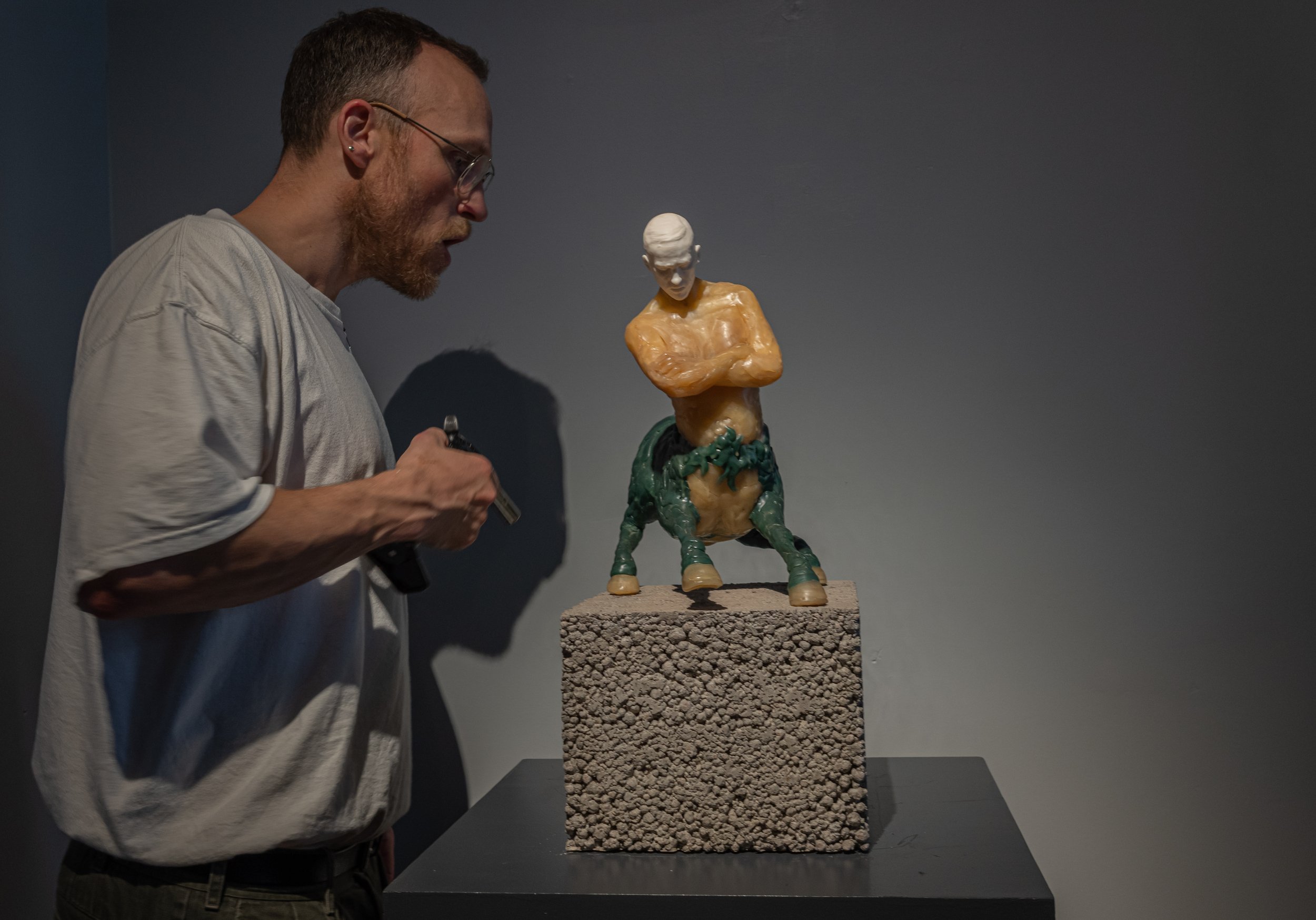

Inspired by the art he encountered on his travels through the mediaeval towns of Scotland, England and Belgium, James B. Webster, as a sculptor, was keenly interested in turning some of these illustrations into three-dimensional forms.

Jonathan Kugel

“The context of God’s word and the ignorance of knowledge also caught my attention. There is a vast scope of imagination and “idea” I attempt to play out in materials, my own glazes, and the addition of gold leaf at the very end, which describes the sacred. For this work, I also decided to use terracotta. Having extensively researched art populaire and the glazes used in the last two centuries, I was intrigued to apply this subject matter to these materials.”

James B. Webster

Practical information:

“Bestiary” by James B. Webster

Opening: Thursday 21.09 from 15.00 to 22.00

At Jonathan F. Kugel

Cabinet de Curiosités Contemporain

rue Watteeu 16, 1000, Bruxelles

Opening Hours: Thursday to Saturday from 11.00 to 18.00

& by appointment

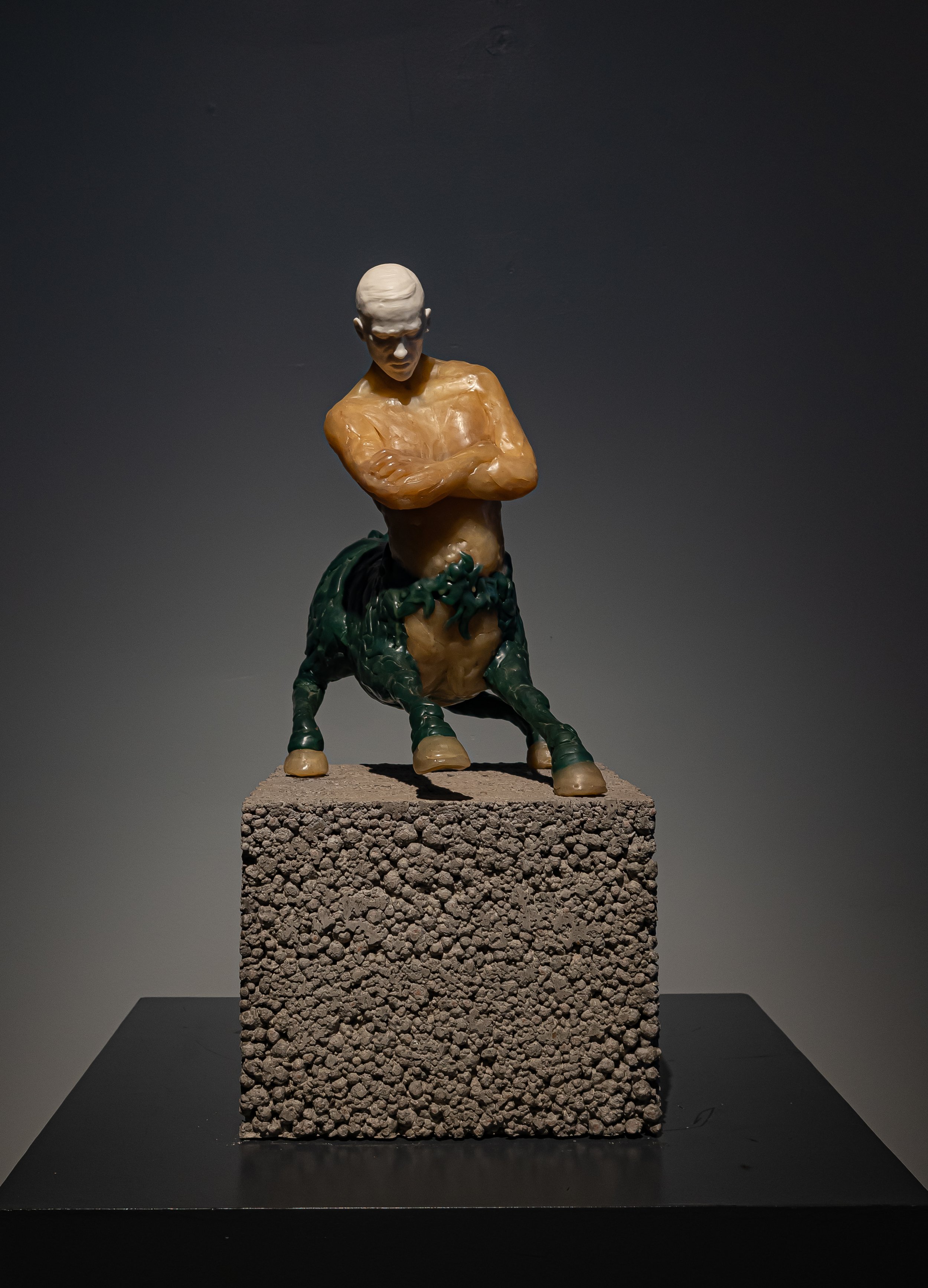

CROCODILE & THE HYDROS - by James B. Webster

Enamelled terracotta and gold leaf, 44 x 44 x 23 cm, 2023.

The crocodile is a four-footed beast, about twenty cubits long, that is born in the Nile River. Its skin is very hard so that it is not hurt when struck by stones. It spends the day on land and the night in the water. It is armed with cruel teeth and claws, and is the only animal that can move the upper part of its jaw while keeping the lower part still. Its dung can be used to enhance a person's beauty: the excrement is smeared on the face and left there until sweat washes it off. Crocodiles always weep after eating a man. Despite the hardness of the crocodile's skin, the hydros can kill it. It crawls into the crocodile's mouth and kills it from the inside.

The hydros is described as a water snake that causes those bitten to swell up, the cure for which is the dung of an ox. The hydros was also confused with the hydra of the Hercules legend, a many-headed water dragon that could grow new heads.

Many symbols are attached to the story of these creatures, the most common being the crocodile signifying hell, and the hydros Christ, who descended into hell to recover imprisoned souls. Another one says that the weakness of the crocodile comes from its inability to make a choice between living on land or in the water.